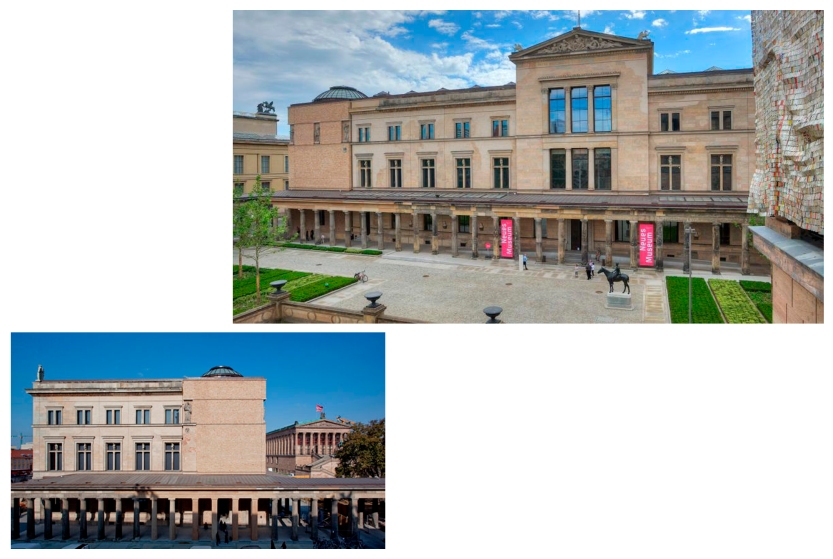

Building Study 006: The Neues Museum, Berlin, 2009. David Chipperfield.

“If I were a poet or a painter I would be a little bit jealous of an architect.”1

Preamble

On the 2nd of October 2017 I was fortunate to attend the Metzstein Discourse, which was organised by the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh. David Chipperfield discussed his work, both in terms of its socio-cultural / architectural origins, and in terms of the reality of the buildings he has conceived. It was an extraordinary insight into the thinking processes, humane awareness, and diligent hard work that has elevated Chipperfield to a position as arguably the leading British architect of his generation. (My thoughts on the 2016 Metzstein Discourse, featuring Peter Zumthor, are described here.)

The Ethos of David Chipperfield Architects’ Work

I have admired the work of David Chipperfield (and his practice) since I was a student at college around twenty years ago. The (apparently) effortless, simple beauty of his work has always been captivating to me – his ability to create elegant simplicity in architecture is something that I aspire to, and something which is at the origin of much of the thinking described in this blog – that blurry line between the ordinary and the sublime:

“I suppose that we tend to look for a certain anonymous quality. I suppose I have an aversion to buildings that are telling you all the time how clever the architect is… I am interested in a sort or ordinariness as well as things being special. I really enjoy that edge between ordinariness and specialness, which is not easy to get.”2

In his talk, Chipperfield described his education, his approach to architectural thinking, and his work in practice. It was clear that there was an inescapable humility and integrity in the way he described his work. He was keen to acknowledge the lessons he’d taken from other architects (referring specifically to Mies, Ando, Shinkel, and Asplund).

He explained that there was, in his view, an inherent “arrogance” in working internationally; given the difficulty any architect would face in trying to understand the unique challenges of working in a foreign environment – and that it was essential to become immersed in that culture, to develop a comprehensive understanding of the place, and the people, so that any project would be entirely appropriate to the place where it was made.

“I think building is a responsibility, and I think it’s a heightened responsibility to build in a different culture, to trespass culturally. It makes you very self-conscious in a good way.”3

There’s clearly confidence and rigour in the work, but the prevailing impression was of a humble architect, committed to the specific, local identities and sensitivities of the places where he works.

Nonetheless, the specificity of the response to each location is contained within a coherent architectural narrative – the fingerprints of which can be perceived across all his projects. So, while there is a tangible Chipperfield-ishness to his work, that architectural vocabulary is adjusted (sometimes subtly; sometimes profoundly) to suit the place where each building is located, and the purpose (and people) which the building will serve.

Reimagining Restoration / The Neues Museum, Berlin

That awareness of place; of the specific social / cultural / historic territory a building inhabits is perhaps illustrated best in the Neues Museum project in Berlin, which was the focus of much of the talk Chipperfield gave for the RSA.

The Neues Museum (New Museum) was designed by Friedrich August Stuller and completed in 1859. It sits on the Museum Island (formerly Spree Island) in Berlin, adjacent to Schinkel’s Altes Museum (Old Museum). The arrangement of museum buildings across the island was conceived as a “sanctuary for the arts and sciences”4 – a cultural depository for the people of Berlin.

The Neues Museum was extensively damaged by bombing during the Second World War. The severity of the damage varied – some decorative interiors survived almost intact, while other areas were completely destroyed – the building had suffered significant deterioration, and was one of the few elements of the Museum Island where the damage from WW2 had not been addressed.

The competition to restore the museum was won by David Chipperfield Architects in 1997, in collaboration with restoration and preservation expert Julian Harrap. The central initiative within the proposal was the ‘re-establishment of form and figure’ in the building.

The analogy offered by Chipperfield in his talk was in the repair of ancient, broken vases. The approach to this problem favoured in many cultures (Greece, Japan for example) is that while the extraordinary value of the original design is not neglected, the material added to reassemble the whole (placed in the voids where the original material is lost) is different. The result is that while the artefact is carefully repaired, there is a tangible acknowledgment of the damage that has been suffered. In terms of building; “the contemporary reflects the lost without imitating it”5.

Chipperfield describes this approach as “soft restoration” which; “keeps everything that is original [no matter its deteriorated condition] and makes sure nothing synthetic creeps in. Don’t take off the render on the face and redo the whole thing. Keep it, paint it, use the same colour – but make sure it is seen to be new. Not glaringly evident but then not faking it either”6. In this way the new works at the Neues Museum are a means to prolong the life of the building in an imaginative and progressive manner; while respectfully protecting the legacy of its original architecture.

The analytical surveying of the surviving fabric of the building was meticulous and forensic. The sincerity of Chipperfield’s engagement with the original building is tangible; there is an extraordinary depth in his understanding of the original fabric – both in terms of its pre-existing qualities, and of the damage the building had sustained. It’s clear that the history of destruction and deterioration was considered to be just as essential to the character of the building as was the original architectural detail, and that sense of decay was respected accordingly.

The extent of the contemporary intervention was informed not by some sweeping, new architectural idea, but by what was appropriate in each part of the building – by a gentle, subtle repair of that distressed material.

His approach is contrary to the prevailing treatment applied by many contemporary architects where, in simplified terms, old is old and new is new – where the architectural friction between each condition is often rather intense. Chipperfield’s restorative work in the case of projects like the Neues Museum is not timid and conservative; nor aggressive and dominating; but rather is based on systematic intelligent analysis of each specific moment in the building.

He is able to understand the relative merits of restoration; replacement; or addition; subject to the particular condition of the space in question. The new elements in the Neues Museum don’t feel like an expression of a broad contemporary architectural intervention, but rather an authentic conduit for the reimagining and reinterpretation of the spatial and material qualities of the original building.

It is a bespoke thesis, which anticipates the implications of every architectural engagement; both in terms of the physical character of a particular space, and the figurative effect over the whole building. In the Neues Museum the result is a kind of hybrid of architectural restoration; blending the preservation of the surviving (but damaged) fabric with the addition of new contemporary elements where the original fabric has been irretrievably lost.

There is a beautiful synergy between the old pieces that have been saved and the new pieces which have been inserted. The result is a compelling narrative which reconciles the particular qualities of the original building; the deadly catastrophe which threatened to destroy it completely; and the more optimistic future with which it now engages.

The Neues Museum project reimagines, and redefines, the capacity of architectural restoration to traverse the physical and temporal space between our past and our future.

Notes:

1 ‘David Chipperfield’; Webster, Murphy, Hutton et al. The Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, 2017. Page 34.

2 ‘Chipperfield’; Philip Jodidio. Taschen, Koln, 2015. Page 8.

3 ‘David Chipperfield’, 2017. Page 19.

4 ‘David Chipperfield Architects’. Thames and Hudson, London, 2013. Page 198.

5 ‘David Chipperfield Architects’, 2013. Page 198.

6 ‘David Chipperfield Architectural Works 1990-2002’; Kenneth Frampton. Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2003. Page 13.

Wow–this is amazing, the words and the images. Thank you for your expertise and for expressing your admiration of Chipperfield. I needed that introduction! Between “ordinariness and specialness”–I just love that. And the vase analogy–that’s one I hadn’t heard before. Wow, such beauty in restoration. I love to see restoration in all things, but especially buildings that suffered at the hands of war. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Rebecca. I’m delighted that you enjoyed this post – his work is extraordinary!

LikeLike

A beautifully written account of an architect and his architecture perfectly understood.

I very much enjoyed reading this post and recalling both the lecture and my own visit to the poetic Neues Museum itself. A must for any student of Architecture.

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is fascinating! I very much enjoyed this post. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I’m pleased you enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the post. Good and strongly built architecture is a need of the time.

I like this profession. My dad was a part time architect in his early days. Hahaa

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Shreya, I’m really pleased you enjoyed this post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful post, thank you for sharing! Such a beautiful building.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Kathryn! I just had a quick look at your blog – I’m a novice admirer, but find your posts very inspiring – following now.

If you have a few minutes, I’d be interested to hear what you think of this, https://dynamicstasis.blog/2017/10/29/the-orchestra/

As I say though, I’m no expert on classical music.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I’ll take a look at your post for sure. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike